ATLAS e-News

23 February 2011

What did it take for a smooth transition?

30 November 2010

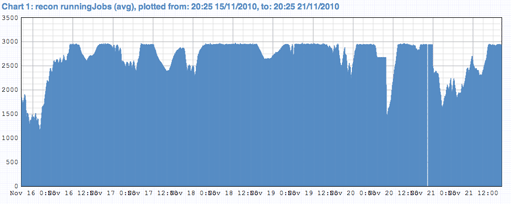

Number of reconstruction jobs running at the Tier0 site last week: running at nearly maximum capacity most of the time.

In the last issue of ATLAS e-News, we reported on what looked like a very smooth transition from proton physics to heavy ion collisions. But how smooth was it? Of course, it all depends on whom you ask, or better, who is in a particular pair of shoes. To find out, we asked Andrzej Olszewski, the Heavy Ion group prompt reconstruction coordinator (PROC) and Walter Lampl, ATLAS PROC coordinator to tell us the story from their own viewpoint.

Andrzej's view:

I have been in the Heavy Ion group software and production manager from the beginning. It has not been always easy to keep in contact with members of our group and maintain software up to date. But when I was asked in the beginning of 2010 to become a prompt reconstruction coordinator for the group, I did not hesitate. I agreed since I just wanted to finish what I had started.

There was a lot of work to get reconstruction up to the ATLAS standards and we are still working on it. We have received help from many software groups, some of their reconstruction and monitoring algorithms had to be adjusted for the special, high particle multiplicity requirements found in heavy ion collision events. In the end, all of this was successfully integrated in a special software release, which is currently used for data processing at Tier0 and for physics analysis.

In July 2010 I was asked to come to CERN and work with Walter in overseeing the prompt reconstruction of the Heavy Ion run. I agreed again since this was a big adventure for me, for the first time being so close to prompt processing of the data taken directly from the detector. However, if I had known how much I would have to learn and how big the responsibility was, I might have reconsidered this decision. Anyway, now that the run is getting close to the end, I am pretty happy that I came to CERN.

There are still challenges ahead of us. The amount of data taken is much more than we planned for. We have to fit the data for analysis within the available disk space in the group areas on the Grid. We have to start raw data processing on the Grid using ATLAS production system in addition to processing at the Tier0 farm. But these issues are relatively easy to solve, group production on the Grid is now routinely run so I am confident that our work will be successfully finished.

Walter's view:

For many months, the Tier0 processed data from proton-proton collisions in a smooth and stable manner. It was almost getting boring. A few weeks ago, LHC switched to heavy ions and things got exciting again. Reconstructing heavy ion collisions poses a different set of challenges from proton collisions.

Only a small fraction of the ATLAS Collaboration works on Heavy Ion physics and only a handful of people are working on heavy ion reconstruction. When the Reconstruction and Data Preparation groups started looking at heavy ion reconstruction in the early summer, I was initially somewhat worried. But there was a positive surprise: Heavy ion reconstruction basically worked out-of-the-box. The small heavy ion group did a great job. There were only minor adaptations necessary like histogram ranges for monitoring plots, except for one big caveat: The memory requirements. Central heavy ion collisions produce an enormous number of charged particles. Reconstruction of all these tracks brings us very close or even above the intrinsic memory limit of a 32-bit architecture machine: 4 GBytes. And of course it also takes a lot of computing time.

On November 5th, just before the first heavy ion collisions, we were pretty confident that reconstruction would largely work. But we also knew about the special challenges ahead: Memory and reconstruction time.

When we saw the first out-of-memory failures at the Tier0, we were not overly surprised. But the real surprise came when we looked at the crashing events in more detail: They were mostly background events, large particle showers coming from collisions occurring in the side instead of coming from the center of the detector. Of course, the reconstruction of some very central collision events ran out of memory, but this occurred only for very few events, and still, they only failed by a small margin. I am confident that we can process all of them with some tweaks. But there is still work ahead to achieve this goal.

Walter LamplAndrzej Olszewski

|