ATLAS e-News

23 February 2011

Closing ATLAS

4 May 2009

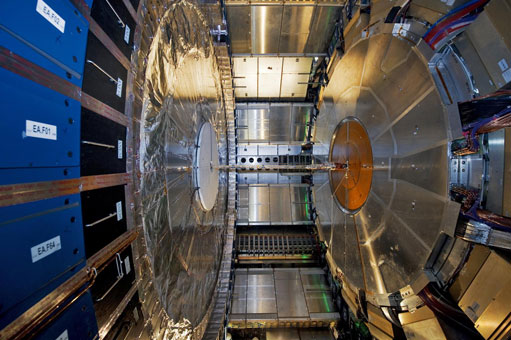

Closing side A, May 2008, but it looks about the same this year (courtesy of Claudia Marcelloni)

Beam isn’t anticipated for another four months yet, but already the giant sub-detectors that together make up ATLAS are carefully shuffling their way into position, taking their places in closed configuration, and waiting for things to start getting interesting.

When you’re talking about high-precision movement of tonnages in the hundreds and thousands, of course, the dance of detectors is necessarily an operation planned to perfection.

Things began on April 6th. Over two days, access to the barrel calorimeter was closed off and all the scaffolding was removed. Next, the end cap calorimeter was eased into position on April 9th, but only momentarily; a failure occurred in the front-end electronics of the barrel calorimeter, so the area was re-opened to allow access for the repairs.

“It would be a pity not to do that,” says Michel Raymond, who is responsible for coordinating the movement of heavy loads in ATLAS. “OK, we lost something like a day and a half in the schedule, but we have a calorimeter which is working instead of a failure that we could avoid.”

As of April 17th, all of Side A was closed. By the 24th, the small wheel and endcap toroid were both in position too. Since then, the focus has been on installing shielding in the forward region, with a few “apertures”, as Michel calls them, left to allow maintenance and improvement work to continue on some parts, for example the LUCID detector.

A project to replace some of the fibres on the monitored drift tubes on the big wheels on Side A will come to an end in the first half of June. The same procedure was done on Side C during the opening phase last October, and should take around a month to complete.

Meanwhile, the closing operation will be mirrored on Side C. “We hope to start by May 10th and complete it around June 15th, depending on what difficulties we meet,” says Michel. Just in time for the magnetic tests which will take place in the second half of June.

The huge components are moved using hydraulic cylinders, which run parallel to the rail that they rest on. Underneath, airpads release the load, which explains how a 1000 tonne endcap calorimeter can be moved using a force of only 23 tonnes.

“We had some difficulties at the first closing [last year] because it was very intensive activity [in the pit] from 2005 to 2008,” says Michel. Now that the detector has been in a fixed open position for an extended period of time, he and his colleagues have been able to get in there to tackle niggling problems and improve the system.

Michel rates the endcap calorimeter as the most nail-biting component to move. It is the most fragile of the moving parts, requires the most accuracy, and has four services chains connected to it which have to follow its movement, driven by a separate electrical engine. The small wheels are a close second, but this time because of their geometry: “It makes them the least stable of the three main detectors that we move,” explains Michel. “It’s been calculated and analysed, of course, but there is always a kind of concern moving them.”

But practice makes perfect, as they say, and the close is feeling much easier this time around: “We’ve improved ourselves at the level of the procedure, at the level of ability, and also the time we need,” Michel confirms, adding, “and of course with the practice, we get more confidence.”

Ceri PerkinsATLAS e-News

|