ATLAS e-News

23 February 2011

31 May 2010

Mahsana Ahsan

Nationality: Pakistan

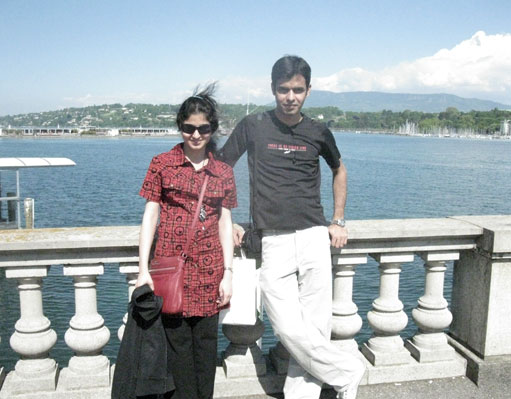

Mahsana and her husband Haleem by Lake Geneva.

For most particle physicists, memories of the dim and distant past when they couldn't yet use a computer are distinctly fuzzy. For Mahsana Ahsan, though, they're a little fresher:

“I didn't have a chance to use computers during my studies due to lack of computer labs,” she explains. “When I first went to the US, I was only able to type an email very slowly.”

In an Internet café in her hometown of Lahore, she carefully put together her electronic PhD application to Kansas State University, picking up technical tips from café staff.

Once she arrived in Kansas, in 2002, she was thrown in at the deep end straight away having to submit an analysis proposal to the grad school, with an example analysis. Although she quickly became comfortable with Linux commands and programming languages, she still notices the disadvantages of not having the technical knowledge base those around her do.

“I feel sometimes this is a little bit of an obstacle in learning and progressing well, in doing things efficiently,” she says. “But with these great collaborations like ATLAS, where people work together, you learn things from other people.”

She may not have known how to use a computer eight years ago, but today Mahsana is responsible for developing a tool used at the Pixel desk in the Control Room. It visualises the whole Pixel system all 1744 modules in one data quality display, so that shifters can get an easy overview of what's going on in the detector, and spot which modules might be having trouble taking good data.

When she got to the end of her physics Masters at Punjab University, Lahore, Mahsana hadn’t even considered a PhD as an option for her. It was thanks to the encouragement of one particular tutor that she plucked up the courage to apply for further independent study abroad.

She credits that same tutor Professor Mujahid Kamran for being the first to pique her interest in particle physics too. “In my first year, I was studying quantum mechanics with him, and I was very impressed with the way he used to throw questions in the class. He kept us very active.”

In her second year particle physics class, Professor Kamran gave Mahsana a book of problems, and told her that once she could work them all out on her own, she would really know the subject. Sure enough, she had managed it by the end of the year.

Professor Kamran has been instrumental in encouraging young Pakistani women to pursue physics.

“I’m very pleased that, after seven or eight years of his efforts, we are seeing some female grad students, post docs, and even one assistant professor,” says Mahsana.

Moving to the US to work on D0 with Kansas State didn‘t only offer academic opportunities that other Pakistani women might have missed out on. “I learned driving there, for the very first time. And I even learned biking [cycling] for the first time!” Mahsana laughs, a little bashfully.“In Pakistan when I was growing up, it was very uncommon for girls to do biking on the street.”

“The US was a completely new world [for me] coming from Pakistan, which is still considered a developing country.” Nowadays, she says, children of both genders are given much more freedom, and girls can even study late in libraries, where before it was unsafe to travel home alone after dark. “The problems are still there, but things are developing.”

Mahsana describes Geneva as “just like a paradise” where she enjoys spending time down by the lake, browsing the shops, walking from place to place near her home in Saint-Genis, and sampling the local cuisine:

“It‘s really like a nutritious food, especially compared to the US!”

She began her post-doc here in July 2008, with the University of Texas at Dallas. Beaming, she explains that her husband of six months has just arrived in Geneva to join her, after they have spent over a year mostly apart while he studied in Karachi.

Right now, Mahsana is developing her analysis code, ready to begin a search for dark matter once ATLAS has collected enough data.

“There are lots of dark matter theories, but [the one I'm working on] just appeared in 2008,” she explains. “I basically wanted to do some search. Because the LHC itself is a very new experiment, I want to discover something that has never been discovered!”

Ceri PerkinsATLAS e-News

|