ATLAS e-News

23 February 2011

Getting the picture

14 December 2009

First collisions in the Control Room

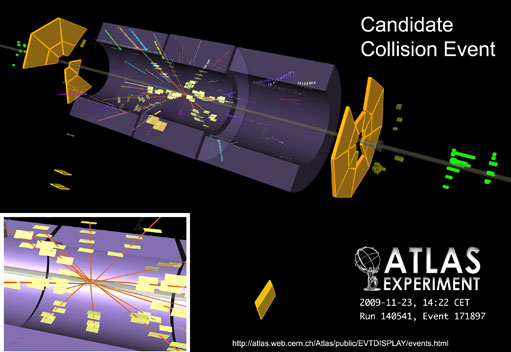

There is a certain 3D image – and you know which one I mean – that will be etched on the memory of every ATLAS collaborator for the rest of their lives. The purple and yellow Inner Detector, with a rainbow of tracks emanating from its centre, illustrates the first ATLAS candidate collision event – Event 171897 – that was shown to a packed Control Room and, soon after, the world on November 23rd.

A couple of hundred lucky individuals waited eagerly in and around the Control Room for these first glimpses of their detector on track, and many more sat at their workstations all over the globe. Meanwhile, a crack team of nearly 20 individuals were holed up in the data quality satellite control room upstairs, tasked with identifying the first good events as quickly as possible, and then unleashing the full power of the graphics programs on them.

The dedicated scanning team was made up of reconstruction and graphics experts from right across the board, explains person-in-charge, Markus Elsing: “The muon software coordinator, ID software coordinator, people from the calorimeter, graphics experts, trackers, the PROC coordinators... all sitting together. All with thousands of other things to do normally,” he laughs.

While everyone downstairs held their breath, tensions were rising upstairs, as the pressure to pull a decent event image from the data before the 14:00 press conference mounted. The machine people had already warned that the beams wouldn’t be brought into collision before noon, meaning time was extremely tight. But, around 13:00, says Markus, “We looked at the first events and saw that the machine wasn’t really colliding, it was all beam gas or beam halo events going splash through the detector.”

It was 14:15 before the beams were adjusted well enough to produce better events. By this point, things had got a little crazy, and the satellite control room was swamped with bodies as the scanning team tried to work. “Everybody was shouting event numbers out, looking at events from the event server that could have been collision candidates. Then everybody was trying to look at these events in more detail,” describes Markus.

While some checked the timing of the minimum bias trigger scintillator hits, to determine whether or not measured particles were originating from a central interaction point – a tell-tale sign of a true collision event – others were keeping an eye on what the tracking was doing or were performing feats of heroics – cue Sebastian Böser, reviving a floored online event server in possibly the most stressful 15 minutes of his life so far.

“The DAQ people downstairs were also scouring and pushing events manually so that those upstairs could take a look,” says Markus, which explains why, at around 14:00, he could be seen running up and downstairs between the two workspaces, trying to maintain the connections between everyone doing different things.

“You want to have something to show which is really a gold plated event,” he explains, “but we knew we were somewhat on the edge with what we could do to actually get good events.” With the Pixels off and the SCT on standby at that stage, and problems with the tracking in the heat of the moment, the team had limited information with which to judge the events they were seeing.

It’s pretty astounding, then, that the event that they actually selected to show – seen at 14:22 – was actually only the third event out of a final total of almost 200 collisions recorded during the run. “So we were actually really efficient at getting the first very nice event!” grins Markus.

First reconstruction of a candidate collision

After ten minutes discussion with Deputy Spokesperson Dave Charlton, Markus had enough confidence in the event to hoist it onto the screens in the Control Room, run it over to Fabiola at the press conference in the Globe, and upload it to the internal collaboration webpages. At 21:00, after Alice, LHCb, and CMS had all also recorded collisions, the event image was made public.

“I think ATLAS has the best displays of all the experiments, and that’s really down to the enthusiasm and dedication of just a small group of graphics developers,” Markus says. “They really know how to manipulate the graphics to actually show the details we want to see.”

Now some of the pressure is off for the scanning team, at least until the same task is required of them again on the day of the first high-energy collisions. In the meanwhile, as well as tending to their own areas of the experiment, they have begun to systematically go through the recorded events, with the aim of debugging and understanding the detector. Already, a di-jet event was spotted in the data, although the consensus that it was indeed a jet event was only reached two hours before Andreas Hoecker showed the plot in his address to the whole of CERN.

“Most of the plots he showed were like that,” smiles Markus. “Basically, everybody was working day and night. It starts feeling like an experiment now, and that’s really, really cool to see.”

Ceri PerkinsATLAS e-News

|