ATLAS e-News

23 February 2011

Operation tasks in ATLAS – what, why and how

28 July 2008

Everybody on ATLAS has to take their shift, without exceptions! Muriel was shift leader this morning, getting a report from her crew.

Already two years ago it was recognised that taking care of a complicated detector like ATLAS, online and offline, would require a very large effort. Institutes and individuals expressed concerns that this effort must be well defined, planned year by year, and fairly shared among the collaborators.

As a result, a Collaboration Board working group under the leadership of Norman McCubbin studied the issues and provided a report that established the concept of ATLAS operation tasks.

An operation task (OT) was defined as a task associated directly with the operation (including triggering) and/or maintenance of the ATLAS detector, or with off-line processing, but not ‘physics analysis’.

The report suggested a sharing model based on the number of ATLAS members in an institution who are qualified as authors or are in the process of qualifying, with students weighed by 0.75. Slightly higher loads are imposed for new groups joining ATLAS. The final fair sharing is implemented per funding agency.

The numbers to be applied for year N should be based on the number

of members on 30th September of year N-1.

The report was approved by the ATLAS Collaboration Board February 2007.

At the same time, the lengthier process of defining these tasks was started with the project leaders and activity leaders (the leaders of the operation, trigger, data-preparation and computing areas). For each sub-system, OT include shifts, running calibrations, data-quality

monitoring, and maintenance of the sub-system and its associated infrastructure.

These are ‘system-specific’ OT.

There are also OT that cover the main activity areas, eg run-co-ordination, general shifts, common system tasks, common infrastructure, safety. These are ‘general’ OT.

In addition, OT include Trigger operation, Data Preparation (i.e. calibration and

alignment), Computing (i.e. reconstruction of data, production of large-scale

Monte-Carlo samples, etc.) and maintenance of the ATLAS software and

associated software infrastructure.

For each type of OT, there is in general a further distinction between an ‘expert’

task, which requires a long learning-curve and/or deep knowledge of a particular

area, and a ‘shifter’ task, which a ‘normally competent’ member of ATLAS

can learn to carry out within a few weeks. Some tasks will require presence at

CERN, some will not. The process of estimation and allocation of OT is overseen by a small panel

(Panel for Operation Task Sharing: POTS), appointed by and reporting to the Collaboration Board.

With very good help and support from the CERN IT division, a WEB based tool (Operation Tasks Planner – OTP) to enter and plan tasks was developed. The data kept in the OTP database are the number of hours spent by any ATLAS member, (defined as being identified in the ATLAS member database), on operation tasks, with his/her correct institute and funding agency connection.

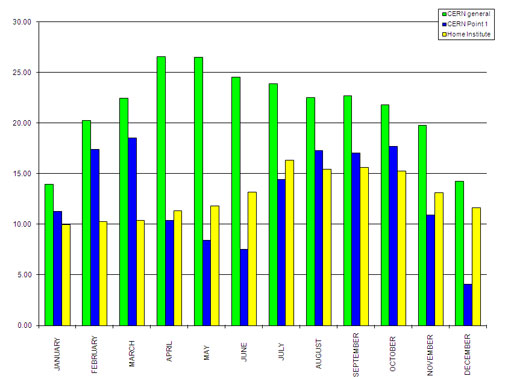

Locations of tasks – an example of the kind of statistics one can now extract from the Operation Tasks Planner. This plot also illustrates that one does not have to be located at CERN to perform various operation tasks.

Locations of tasks – an example of the kind of statistics one can now extract from the Operation Tasks Planner. This plot also illustrates that one does not have to be located at CERN to perform various operation tasks.

Today most operation-related activities in ATLAS have been through one or several iterations of planning the tasks, estimating the personnel needed, and filling names of the responsible person. The tool is used by 30-40 shift-managers – to plan and allocated shifts, actually the shifts are booked by individuals in the same way they book flight on internet, but free of charge.

More than 600 full-time equivalent tasks are described with less than half currently filled. The major obstacle today to complete the overview and predications for 2008 is not that planning is not made, but many tasks and names are not entered using the OTP tool.

The potential benefits of the system are significant, as it forces careful planning, a good overview of personnel needs and allocations, uncovers weak areas, ensures over time fair sharing, and provides a unique record of who is doing what in ATLAS. It has also uncovered many database problems with people working happily in ATLAS but not being correctly entered in our members database.

The negative side-effects observed are that many people spend too much time worrying about special cases and borderline tasks. The most useful advice is that the OTP allows keeping track and documenting something that would need to be done in any case, so it should not change the responsibilities of any of us on a short time scale. In long term, it becomes a tool to strengthen weak areas, reduce other areas, and for institute leaders, a tool to plan their groups future activities in a coherent way with the people responsible for various operation areas.

Reports are slowly becoming available. It is re-assuring to see that data entered in a database can in fact be extracted and presented in a consistent form. Examples are individual assignments, assignments per project, per group, per funding agencies – which in turn can be compared with expectations. These reports are still in the process of being finalised. Lots of statistic are also becoming available about tasks, requirements, tasks location, nature of tasks, etc.

Every ATLAS member should therefore now secure their OTP mileage now, for the good of ATLAS and their own participation in ATLAS. Three main steps are needed; 1) make sure your operation activity is registered – 2) ask you project leader or activity leader if your work is entered and recognised, make yourself available for shifts – 3) talk to the people arranging shifts and make sure you become trained as a shifter (and don’t hesitate to take on those with high responsibility), and finally when call for shifts are made - sign up as soon as possible.

Steinar StapnesUniversity of Oslo, Norway

|