ATLAS e-News

23 February 2011

A day in our shoes

6 April 2009

A group from Rutherford Appleton Laboratory's program

While many students aren’t introduced to particle physics until they reach university, the International Particle Physics Masterclasses are on a mission to change that, offering students between 16 and 18 years of age the chance to step into a researcher’s shoes. This year’s international program involves 6000 students from over 80 institutes in 23 countries, including much of Europe, with groups in Brazil, South Africa, and the US. A local sub-program run by Quarknet in the US includes another 22 institutes.

“Students should come as early as possible in contact with the fundamental questions about our universe, get their hands on real data, come in contact with scientists, and experience how fascinating physics can be,” says Michael Kobel, the global organiser of the masterclasses. Within the European Particle Physics Outreach Group (EPPOG), he worked alongside Christine Sutton of the CERN Press Office and Erik Johansson of ATLAS to first extend the Particle Physics Masterclasses to Europe in 2005, the World Year of Physics.

At Rutherford Appleton Laboratory in the UK, the country where the program started in 1997, approximately 500 students participated in the three one-day masterclasses. The program has a broad range as far as student counts at each institute; in Helsinki, Finland, the students numbered thirteen this year. No matter the program size, the students start the program with lectures, introducing them to ideas in particle physics. Depending on the location, students might get a tour of the facility.

Once students have learned the basics of particles, detectors, and the Standard Model, they get their hands on real data through web-based programs. They work in pairs, applying what they learned earlier to identify particles and processes, and at the end of the day, they have the opportunity to share their analysis with other students from institutes around Europe or around the world.

They can find the branching ratio for Z0 decays in DELPHI or exclude the background in ATLAS events by examining images of real and simulated particle tracks. The Minerva set-up allows students to view simulated particle events through Atlantis, the same event display that we will use to find new physics in ATLAS.

Communicating through Caltech’s EVO system, the students participate in discussion of the data and a ten-question quiz on particle physics. As one of the program’s main goals is first-hand experience as a particle physicist, many groups also encounter the familiar tech problems that accompany video conferencing.

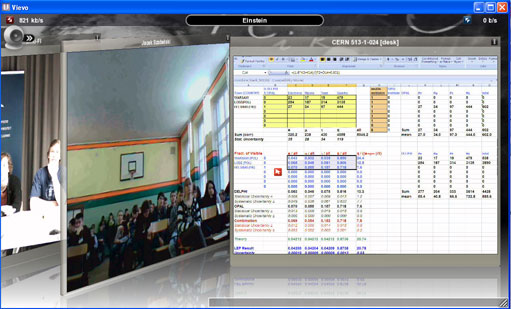

Groups from Helsinki and Lodz share and discuss their results, led by moderators at CERN

Students on the standard agenda share their data at the end of the day. However, it takes some careful planning to cross the time zones between Europe and the Americas, requiring students on the west side of the Atlantic to conference in the morning on a second day. “We tried to foster this kind of international exchange, but for most sites it is difficult to organise it,” says Uta Bilow, coordinator for this year’s international program.

For many classes, the day is long – a group from Helsinki reported six hours of lectures and two hours of data analysis. It is an intense program, but 82 per cent of students report that they enjoyed their day as a particle physicist. The fact that program enrolment has doubled since it originally went international in 2005 speaks strongly for its success. And, with just four per cent finding the material too easy or too difficult, the instructors have managed to pitch the challenging material at just the right level.

Glenn Patrick of RAL says: “Over 70 per cent of the students from the first day said that they were more likely to consider a career in physics or science as a result of this event.”

Correction (7 April 2009): The final quote was wrongly attributed in the initial article.

Katie McAlpineATLAS e-News |